Silicon Valley is a place and a fantasy. The place is the unceded lands of the Ohlone, Coast Miwok, Southern Pomo, Bay Miwok, Patwin, Kashaya, and Mishewal Wappo people. The fantasy is opportunism masked as optimism, summed up best by Zuckerberg’s slaphappy motto, “move fast and break things.” Unveiled, this fantasy is simply the settler economy, one based in the predatory speculation of stolen land and the extraction of rare earth throughout the Global South. Shrouded in the technofascist mythos of social Darwinism, technical expertise, and design thinking, Silicon Valley appears less a harbinger of the future and more an iteration in a long history of speculative extraction, of land, and minerals from long before the 1849 Gold Rush all through the 1990s dot-com boom.

Growing up in the Valley, we came to see that the “American Dream” is a securitized dream. The long Cold War—the escalation of U.S. military occupiers into Asia and the Pacific, the originary accumulation driving the subsequent “brain drain” of tech workers from formerly colonized territories—puts delusion and lived reality into ever sharper relief. This contradiction is the origin for Cold War diasporas (our parents among them, from Taiwan, Korea, and Singapore) that then make home in the ethnoburbs latticing the Bay Area: diasporas born of militarism, now conscripted into laboring for the militarized industries of empire.

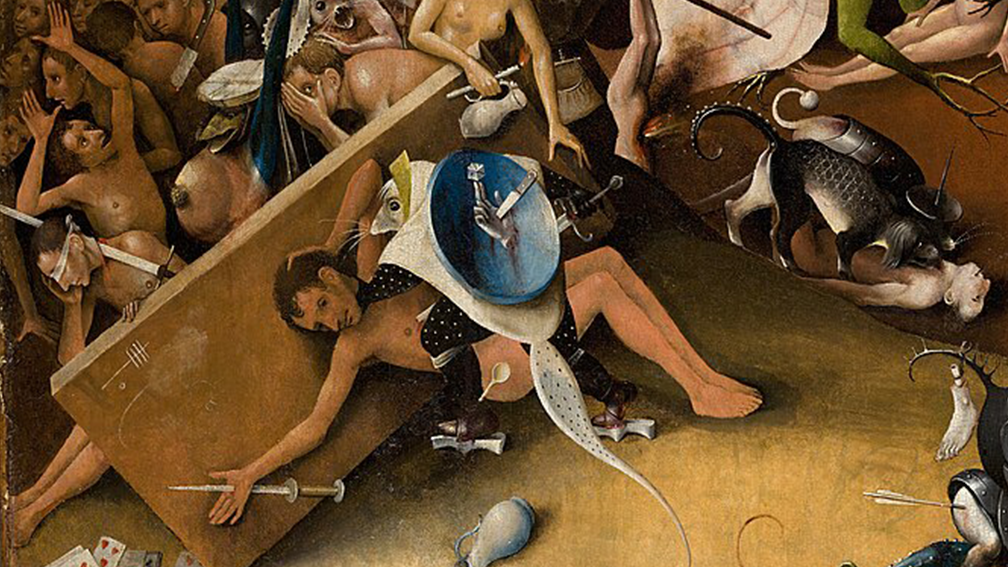

Despite the war economy that has driven Northern California’s suburban sprawl, the sprawl remains a home. Over the course of three months, we embarked on a “remote tour” of Silicon Valley through a series of postcard exchanges over email. We returned to the rise of tech conglomerates from the sludge of the early chip economy; the incessant construction of new high-rises-cum-factory towns; the K-12 coding camps and the on-campus recruitment fairs for the largest arms dealers in the country; the tunnels beneath the parks, the tunnels harboring poisoned creeks, the drives past the shut gates of secretive military outposts. We ask: What do the ruins of Silicon Valley tell us about the production of waste and disposability? How does the war economy depend on detritus, from military ruins to microchip emissions? And what about the land that undergirds Big Tech–soil, water, and rock as grounds of present and future renewal?

basalt h. + sm downer

01/25

s.m.,

When I return to the Bay Area, I return to Stevens Creek. The creek begins from the Santa Cruz Mountains and empties into the San Francisco Bay near Google's main campus. In my high school years, stoners, punks, and posers would hang around the bends of the creek, which ran through my neighborhood and along an expressway by my elementary school.

The Stevens Creek watershed once served as a source of freshwater before it became a dumping ground for semiconductor manufacturers in Silicon Valley. The earliest of these manufacturers was Fairchild Semiconductor, which got its start creating silicon transistors for military use in the 1950s. Wherever Fairchild went, labor strikes and groundwater contamination lawsuits followed. In the 1960s, Fairchild opened up assembly plants in Hong Kong and on Navajo Nation’s Shiprock reservation, launching the development of an “offshoring” strategy that cut down labor costs on the one hand while evading environmental protection laws on the other. The waging of war is simply inseparable from the exploitation of labor and designation of sacrifice zones.

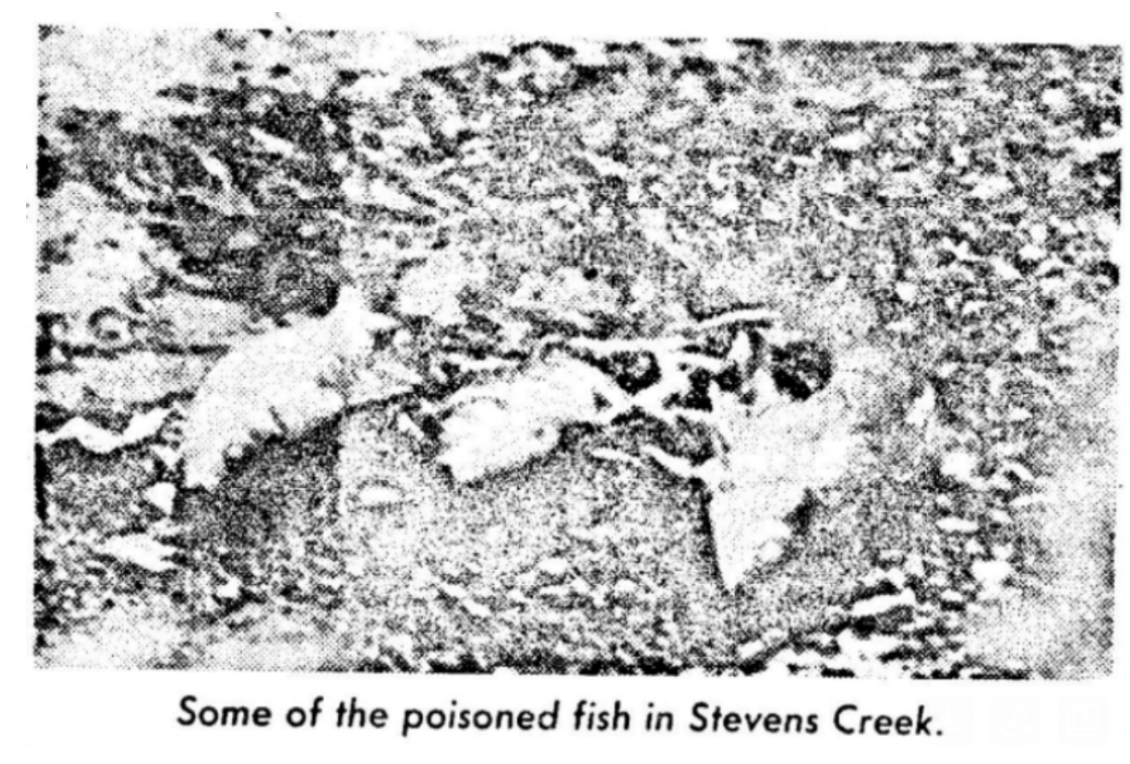

Minuteman interballistic missiles were downstream from the semiconductor manufacturing supply chain; upstream, companies like Fairchild dumped acids and solvents into storm drains. Beneath the smooth concrete of suburbia, these corrosive fluids ate away at underground pipes over the course of decades and bled into the Stevens Creek watershed. I’ve included a newspaper clipping about a chemical spill in 1978 from Fairchild: in Mountain View.

Did I mention that Fairchild Semiconductor’s parent company was responsible for developing technology for aerial military photography? Meanwhile, on the ground, we lack clear imaging of the water and bodies poisoned by weapons industries. The grainy photograph of poisoned fish in Steven's Creek chafes against the frictionless image of Silicon Valley's economy. It chafes against the rise of "light" industry, semiconductor "cleanrooms," and the immaterial "cloud,” Big Tech vocabulary that sanitizes the century of military contracts binding toxified bodies to toxified minerals to toxified soil.

Resting at the mouth of Stevens Creek, Google is a tomb. Its billion-dollar headquarters sit atop the superfund sites created by semiconductor manufacturing companies like Fairchild. Learning about the Bay Area’s Stevens Creek led me to another Stevens Creek in Dimrock, Pennsylvania. Decades after the Fairchild spill poisoning the West Coast Stevens Creek, hydraulic fracking has poisoned wells and ponds along this other Stevens Creek on the opposite side of the country. In Dimrock, water from Stevens Creek once used for farming and drinking has become undrinkable and even flammable.

This year, I realized how little I knew about our drinking water. Where it comes from, where it goes, how it is diverted, what it feeds. I remember the headlines every time Taiwan experiences a drought: What about the chips?—whereas, the mangos, lychee and longan, bamboo, eels and tilapia…

01/25

basalt,

Poisoned fish, flammable water. I read your note while watching flames char the Pacific coastline on my phone. There is the ocean, caressing the carnage. And yet there is not enough water pressure to put out the fires. In Bakersfield, California, there is a bank that holds 1.5 million acre-feet of water. A majority stake belongs to the wealthiest farmer in the United States, who turns out to be two people: the Resnicks. Is water home and kin, or is it an asset, worth billions? As aquatic fortunes fuel the genocide of Palestinian people and the theft of their homelands; as do roasted pistachios, pomegranate juice, flowers, citrus, and Fiji Water; as I dreamt of olive trees. The people in the boardrooms and the backrooms call it disinformation–that it’s all water that would have been “lost to sea”; that a genocide of an entire people constitutes “nothing to see” in the so-called Global War on Terror, a racial scheme within which the imperial core attempts to shield itself from becoming a target.

Imperial disavowal in the form of disinformation campaigns in the form of data streaming in the form of running water. Since learning about the water it takes to power a single AI search, I've considered how apt a metaphor "the cloud" is for the internet. From thirsty servers to thousands of cables trawling the ocean floor, the infrastructures of the World Wide Web can be mapped onto every phase of the water cycle. Do you remember the Diamond Princess from 2020? The cruise ship from Yokohama-turned-quarantine-zone, stranded at sea? (Literally a nightmare, if you ask me.) The government flew American passengers from Yokohama Port to Travis Air Force Base, 60 miles north of San Francisco.

Travis has an active partnership with California’s private developers: Since 2018, a clandestine class of Silicon Valley investors has purchased tens and thousands of acres of the arable land around the base. The goal? To build a "city from scratch." "California Forever" is what they'll call it—a utopian "clean energy" metropolis built on stolen land otherwise capable of sustaining generations. Whole lifeworlds boiled down to a scratch in the earth, a starting line of an imaginary race to the stock market, to outer space, to the end of the world. I'm reminded of what Octavia E. Butler wrote about utopia stories: "I don't believe them for a moment. It seems inevitable that my utopia would be someone else's hell.”

02/25

s.m.,

Building a "city from scratch"—when the material of “scratch” is the acres of expropriated farmland, the conditions being the intensive displacement of Black and brown tenants and mortgage-holders required to make Solano into a blank slate. Fantasy displaces even without breaking ground, driving the predatory speculation that turns land into the raw material for soaring profits.

I’m struck by how Butler points out the dialectics between utopia and hell. It reminds me of how "utopia" originates from fictional islands of a fantasy society. Meanwhile, the Bay Area's actual islands form carceral archipelagos, from Alcatraz to Angel Island.

Of the many descriptions of Alcatraz—as FORT as MILITARY PRISON as PENITENTIARY as PRISON TOURISM—the one that stands out most is ROCK. Something barren, something incapable of life. So much state documentation claims there is no record of activity on Alcatraz before Spanish colonization. This logic produces so many "uninhabitable" islands (from California's Alcatraz to New York's Rikers to Peru's Chincha Islands to the South China Sea) into spaces of military occupation, of carcerality, of settler isolation. Yet the "uninhabitable" conditions of each island produces its own demise. Consider: The Alcatraz prison compound was staggeringly expensive to maintain because of constant erosion from salt spray. This place was never meant to hold concrete and metal! The island rejects the settler project.

Then if I think about ROCK another way—as anchor, as steadfastness—a whole other side of history is illuminated. Ohlone people used Alcatraz as a fishing station; even its colonial Spanish name comes from alcatraces, or the gannets that would nest in these "uninhabitable" islands. It was also safe harbor for Native people escaping Spanish missionaries. There's a lesson in these islands as migratory nodes, as places of refuge, as places that fed—not to be owned or permanently settled. It wasn't always so inevitable for Alcatraz to become a site for prison tourism. I think of the generations of First Nation prisoners of settler war who were held on Alcatraz—and the key few who would be able to return decades later to join those displaced by the Indian Relocation Act. Together, they would form the Indians of All Tribes (IAT) and occupy Alcatraz in 1969. ROCK as the birth of the Red Power movement, stoking the flames of the growing Black Power movement. During IAT's 19-month occupation, Assata Shakur would visit as a medic and invite IAT to Harlem. "Sure," they said. "When are you going to liberate it?"

Native students decided to get organized and occupy Alcatraz after a fire destroyed the San Francisco Indian Center. In the Rider-Waite tarot deck, the Tower card is depicted as a tower on fire. Christopher Marmolejo writes in Red Tarot: "The tower targets not only the annihilation of the property of plantation and prison, but also annihilation of the property relation that is whiteness." In the Bay Area, where Big Tech is simply the latest settler force, Alcatraz is the tower on fire.

03/25

basalt,

“Uninhabitable” raises so many questions: according to whom, by which criteria, during which seasons, for what reasons. How many lands and waters deemed uninhabitable have been targets of US imperial war—firebombed, irrevocably irradiated, stolen and eviscerated?

There's a reserve military base in Dublin, Camp Parks, that I used to drive by as a teen on my way to the BART. Commissioned in 1943, the base was one of three that made up "Fleet City," a network of military processing, housing, training, and medical facilities designed to receive and deploy US soldiers fighting in the 20th-century Pacific wars. In 1951, the Navy transferred ownership of Camp Parks to the US Air Force, which used the base to launch aerial warfare campaigns in Korea (and later, to the Army to train soldiers being deployed to Vietnam). That same year, Alameda County purchased the old Navy brig, repurposing it as the Santa Rita Jail, which is today notorious for boasting the highest number of in-custody deaths in Northern California.

Like "uninhabitable"—imperial destruction naturalizing itself as absence of habitat—the term "in-custody deaths" performs a sleight of hand: state-sponsored murder posing as custody and care. This is how traces of the American Dream’s original expropriation leave their mark on our daily architecture, from the homes we grew up in to the language we inhabit. Less common now, Quonset huts once dotted the Bay’s postwar landscape. Corrugated plywood-steel semicircular structures, engineered by the military for lightweightedness, packability, and replicability, Quonset huts contain in their name a theft from Quonset Point, in Namcook (Rhode Island), where they were first constructed; "quonset" being Algonquian for "small, long place."

We’re back to the dialectics of utopia and hell: The standard half-acre suburban front lawn depends on the six-by-nine-foot cell of solitary confinement. And then there is the question of how to bring this circuit to a halt. On the evening of July 17, 1944, "[p]eople throughout the Bay Area awoke to something that felt like an earthquake--a blast with the force of five kilotons of TNT," according to Matthew F. Delmont, with sailors fearing "another Pearl Harbor." Slipshod safety protocols had exploded two munitions ships at Port Chicago, 36 miles northeast of San Francisco, killing 320 people. Among the dead were 202 Black enlisted sailors who had been assigned to move thousand-pound bombs with little to no training. As a result? Fifty Black American sailors staged a work stoppage; they were arrested, threatened with the death penalty, and ultimately convicted of mutiny. They served years at Terminal Island military prison south of Los Angeles.

A flash of unbearable heat. Scattered limbs. Unrelenting grief met with the threat of the death sentence, dropped like a leaflet on the people shipborne bombs are intended to kill. The tower on fire, followed by the terminal island, followed by ?? What comes after the terminal island? Where else is ROCK?

In a video of a settler’s bulldozer, churning the road to rubble. In the erosion of Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary under the slow, steady pressure of sea spray. The IAT who occupied Alcatraz for 10 months. The 50 who refused to move weapons for the world’s largest military, knowing they could be used to kill their own. The six Palestinian prisoners who dug themselves out of the Gilboa prison with plates, a kettle handle, and spoons.

03/25

s.m.,

Liberation by any means necessary—these days I struggle to remember that it is when empire is in its dying throes that it strikes with ever greater desperation. With the DHS and ICE abductions, I've been thinking about how the security apparatus, the surveillance technologies that target organizers— from the 2020 uprisings, from Stop Cop City, from the student movements for Palestinian liberation—simply would not be what it is without Silicon Valley and its patronage of Unit 8200, the cybersecurity and cyberwarfare arm of the Israeli Occupation Forces. The technological advancements of settler states appear to have no limits: the development of ChatGPT-like language learning models to surveil and intercept messages in occupied territories, repeated attempts to deploy facial recognition programs at Gaza's borders, etc. And yet, the fantasy of undefeatable power falls apart. The rock strikes the tank. The spoons break from the high-security prison. The paragliders breach the border. The fact is that even the billions of dollars poured into military technology do not guarantee greater precision or undefeatable might.

Al-Aqsa Flood, the Gilboa prison break—these are ruptures in the weapons supply chain much later down the line, at the very moment when the military or counter-intelligence arm deploys the weapon. Silicon Valley is located at an earlier point in the supply chain: research and development, the point of human resources.

I can't help but go back to my childhood cartography. In San Jose, I remember police precincts and military recruiters on my campus quad. I also remembered students whose parents scored them a summer internship at Lockheed Martin. I remember the recruitment fairs, the robotics contests, the NASA-sponsored field trips, the summer internships at Google, the billions in STEM funding from k-12 to college campuses to research programs. The eugenicist origins of Stanford, from Leland Stanford's horse-racing/horse-breaking kindergarten tracks to IQ tests. R&D science parks that sculpt the Bay Area, from San Francisco to the East Bay to the South Bay. The way defense technology companies prey on student debt under the guise of DEI. The way ROTC shapeshifts into loan forgiveness at Lockheed, at Raytheon. One summer I did outreach in San Jose near Moffett Field—a federal airfield that was established in the early 20th century as the first Naval Air Station in Silicon Valley. For years, working class and immigrant families living around Moffett have been organizing to shut down the airfield. Their children have been getting sick from the relentless noise and pollution produced by military fighter jets and airplane cargo. Children of immigrants displaced by U.S. imperialism–are they casualties or targets? And what about the Black sailors killed by the TNT explosions at the Port of Chicago? The reality is that preparation for war is war itself. The Black sailors organizing work stoppage halted the making of war across borders. This is why the state responded by jailing the sailors on strike. By jailing them, the state not only delivered punishment but also made it lucrative, redirecting the flow of profits for the war economy by filling the cages at home. When will the fantasy of undefeatable power shatter? What do we have to put down or take up to destroy the mirage?

04/25

basalt,

Today I'm writing you from Jeju, another terminal island where, in 1948, a massacre perpetrated by the South and facilitated by its US military patron stamped out a multi-year uprising protesting separate elections and thereby Korea’s permanent division, leaving one out of ten islanders dead. Today, Jeju remains marked as a "Red Island": a so-called communist stronghold, but also one that has been washed in the blood of illegitimate occupation. Being surrounded by water reminds me of the Pacific coastline, where the mundanity of war is borne by the earth. From the steel ruins of defunct continental railroad tracks, constructed by coolie labor; to the R&D-driven pavement parks that stipple today's Bay in exchange for municipal funding; to the rise of ChatGPT and fascist AI art that treat the world as a series of surfaces, the ethos of "move fast and break things" at the core of silicon capitalism finds its limit in the land, the sea, our bodies; in our collective porosity.

Camp Parks was one of numerous designated cold war nuclear testing sites across the United States and its imperial conquests. From 1959 to 1980, the Navy and the Office of Civil Defense exposed people, plants, and animals to radiation, from growing crops in soil shocked with plutonium to raining irradiated sand onto rooftops to simulate nuclear fallout. One local hired as a shepherd recalls being tasked with burying irradiated sheep, sans protective garb, and how "their limbs would fall off in his bare hands." In 1983, his daughter was born without a trachea.

From superfund site to aerial target to company plaque, every surface is a record of depth. So there’s something ironic about the fact that tech moguls are begging to be launched into outer space; that venture capitalists assume the title of “angel” investors; that Santa Monica’s tech bros keep squandering precious planetary years on commodifying literal sunlight. Once you’ve extracted all there is on earth, where else is there to go but up? Bezos in a rocket, the aerial view from the cockpit: It’s death drive shit.

What David Harvey calls the spatial fix (naming how capital overcomes crises of overaccumulation by relocating from place to place) perhaps finds in dissociation its psychic mirror. US imperialism wages fragmentation upon our relations, dispossessing whole peoples of their land and histories, depending on the distance of decades to suture the irreparable wound. Yet, to quote Thuy Linh's Tu, wartime is "less a temporality than a sensibility” that has little regard for the passing time. The war for our attention isn’t just happening on our screens–every war is a phenomenological and epistemological struggle over how to sense, and make sense of, the world.

Writing to each other, these postcards attempt to tune into the frequency below the clicking and the whirring, to the seeping and the stirring–the poisoned creek, the buried limbs and sheep, the imperial ruins beneath, above, and everywhere around. An homage to taking the long way home. In that space of suspension, the technocracy’s fantasy of frictionless progress grinds to a halt. The refusal to load munitions or to program apartheid; the defacement of harms dealer headquarters and the rematriation of stolen land; the undamming of choked rivers and the prison break launched from the river to the sea. We follow the chorus of refusals and organized resistance to the place of mending— less a place than a process of wayfinding within ruin; mapping our relations with the dead and the living; inhabiting the time of rock, roots, and sea…