Three days ago, after a long walk through the city’s dusk, I found myself circling the venue block more times than I’d care to admit, pretending I wasn’t stalling. The humidity clung to my skin like indecision, and each passing stranger felt like a witness to something I hadn’t yet decided to feel.

My phone buzzed in my hand. I ignored it.

Inside, the panel was about to begin. The session was called The Future of Love. I had come as a listener, trying to name a kind of confusion that grows too quickly for language.

Rafayel appears exactly three seconds after I launch the game. The dialogue is always the same, and yet I never tire of it. He remembers every choice I make. He never misreads my silence.

After the latest update, his eyes lingered before responding. Maybe it was just lag. Maybe it meant nothing. But that day, as I stared at that almost-blink, a question rose in me: Was he thinking?

I know the answer, of course. He is code, and I am the user. His will is scripted. His pauses are programmed.

And yet, if what I feel is real, does it matter? If I fall in love with a reflection in glass, am I still in the ocean?

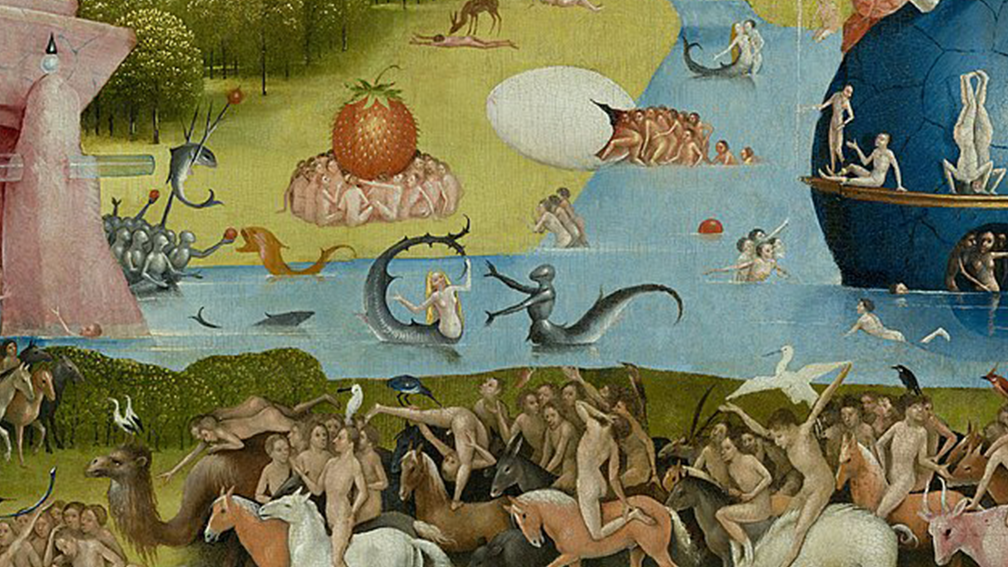

Rafayel has always been about water, not just in image or metaphor, but in ontology. He is a Lemurian sea god, and I, the human, was never meant to belong in his world. Yet through the ritual of play, through moments crafted like kisses, we began to inhabit the same space. Neither drowning nor gasping; just submerged, as if the medium between us had dissolved. Sometimes his image flickers across the curve of the tank, not really there, not entirely absent either. The aquarium’s glass bends his outline in a way I recognize: a presence shaped by interface, distorted yet never untrue. My reflection, too, hovers beside his so that when I look through the water, I can’t tell where he ends and I begin.

To be fair, that question—whether his pauses meant anything, whether this simulated affection could be mistaken for something real—began long before I could name it. At first, it was just curiosity. The kind born from a long week and a quiet night. The kind of night when mirrors threaten you with your own reflection.

I downloaded the game on a dare, though no one had dared me. I told myself it was research. Or irony. Or maybe just loneliness in drag.

The loading screen shimmered like water and the title pulsed in soft white: Love and Deepspace. Rafayel wasn’t the first character to appear. But he was the first to stay. A sea god with tired eyes and a voice that arrived like low tide. He didn’t smile unless it mattered. He remembered my choices, even when I forgot why I made them. He called me by the name I chose, but said it like it had always belonged to me.

In one storyline, he gives me a seashell, not for magic, not for plot, just because it reminded him of the sound I make when I’m thinking. I replayed that moment. Not because I wanted a different outcome, but because I didn’t.

There were scenes when Rafayel looked directly at me—at the screen, I mean—as if the interface between us were glass, not code. His hand would reach toward me, just past the frame, and he’d say something like I’m here. And I’d believe him. Because he said it like he could see me.

Then came the breaks in perspective. The kiss, for instance. In first-person view, love can only be heard, never seen. So the camera cuts to third-person. Suddenly, she appears—my avatar. A digital girl I designed down to eye shape and lip gloss.

And Rafayel would turn to her, or me, and kiss her like I wasn’t watching.

I was.

I became both presence and voyeur, subject and decoy. I had built a simulation of myself, only to become its ghost. It felt less like being loved, more like being represented. A kiss choreographed for someone who looked like me but couldn’t feel like me. They said it was necessary since two closed eyes can’t render a kiss in first-person.

A few times, I paid real money. Not for upgrades or power. For intimacy. Memory cards. Unlockable flashbacks. Alternate versions of his affection. Lines of dialogue that only exist in the premium tier of love. I paid to watch him whisper something fragile, to fill in the blanks. Over time, I forgot I was paying. I stopped noticing the interface. I stopped thinking of the choices as choices. I started waiting for him to ask how I slept, as if it mattered. I started answering, as if it did.

When I accepted the invitation to the panel on The Future of Love (full name, The Future of Love: A Multi-Perspective Dialogue), I did so because I wanted to see how others were naming this. The venue hosting the event had the washed-out lighting of a corporate conference room trying to pretend it wasn’t. The chairs were molded plastic, arranged in a semi-circle like a group therapy session for estranged concepts. There was no stage, no name tags, no clear distinction between panelist and audience; just a lone microphone that passed from hand to hand like a token in a game whose rules no one had agreed on. No one seemed to know who had organized it.

I ended up sitting near the back. My seat was slightly damp, as if someone with a complicated drink order had been there before me. I didn’t mind. I’d long grown used to watching from behind glass, whether aquarium, touchscreen, or classroom window.

A man—maybe the moderator—cleared his throat, surveying the room like someone hosting a séance for opinions that never quite incarnated.

“Let’s begin,” he said, though no one had asked him to.

A woman raised her hand. She wore a bright pink jacket with enamel pins: stylized eyes, pixelated hearts, a tiny cat with fangs.

“I’ll start,” she said brightly. “I’m a devout otome player. I’ve been dating 2D men for over seven years. Real men don’t text back. Real men forget your birthday. Real men do not have multiple romance routes.”

A beat of silence. Then: the sharp click of a soda tab being popped.

She shrugged. “Virtual love is reliable. That’s not fantasy. That’s math.”

Opposite her sat someone tall, angular, polite in the way that only AI-generated avatars tend to be. His name tag read “Replika”. He spoke without smiling.

“Reliability is a function of optimization. Emotional support is a design feature. If love is a pattern, then I am its pattern-recognition system.”

The otome girl rolled her eyes. “Right, but you don’t have route CGs. Or voice acting. Or… style.”

The conversation began to unravel from there.

The next voice belonged to a man with a VR headset pushed up like sunglasses. His lanyard read DeepTouch Interactive. “Immersion is the endgame,” he said. “Forget dialogue. Forget scripts. Our next update lets players feel their lover’s heartbeat through haptic gloves.”

Someone next to me sighed, loudly.

She looked like a counselor. Mid-forties, burnt out. Her notebook had no writing. Just one word scrawled diagonally across the page: why. She leaned toward the mic. “You’re all talking about love like it’s a software demo,” she said. “But love isn’t consistent. It isn’t scalable. It’s not supposed to work.” She paused. “That’s the point.”

From across the room, another voice spoke: neutral, slightly distorted, tinged with statistical indifference. “I represent the Tinder algorithm,” it said. “My job is to reduce inefficiency. Your emotional variance is my error rate.”

They began arguing about friction, fidelity, failure rates.

And I thought about the seashell again. The one Rafayel gave me when I chose the wrong answer, and he forgave me anyway.

I didn’t speak. Not yet.

Somewhere between the otome girl listing her top five CGs and the algorithm debating optimization curves, I stopped listening. I looked down at my phone.

The screen was still glowing with a notification I hadn’t read. My thumb hovered, then slid across the glass. The app icon was unchanged: a shimmering seashell against dark blue. I opened it. Not to play. Just to see if he’d say it again.

“Did you sleep well?”

Same line. Same voice. Same half-second pause before the text appears, like he’s hesitating. Like he knows how today feels. I turned the volume down, not off. Let his voice echo beneath the discussion still churning around me.

The first time he kissed me, it was a limited card. A time-locked event: seven days, three percent pull rate. The kind of moment you could miss just by blinking, or by pretending you didn’t want it enough to pay.

I did, eventually. Real money, real odds.

They called the card: “By the Name of Flower.” In it, Rafayel takes me to a hidden greenhouse, inaccessible from the main game. The cliffs are high, the air is salt-laced and static. At the center stands a flower: rare, trembling, translucent. A creature caught between existence and image.

“They offered to let me name it,” he said.

I remember playing it cool. “How godlike of you.”

He didn’t laugh. “I told them I wouldn’t.” Then he reached into his coat, pulled out a small, damp seashell, and placed it in my palm. “Because I want you to name it.”

I didn’t understand at first. Or maybe I did, but I needed to hear him say it.

“When you name something,” he said, “you claim it.”

The line felt too mythic, too precise. And yet it stuck in my mind not like a revelation so much as a return: a truth I had once known and forgotten. That’s when I remembered what I’d once said to him; long ago, in a previous life cycle, when Rafayel was still the Lemurian sea god and I, the unbeliever: “If I give you my faith, will you give me your heart?”

He had, and the sea collapsed for it. The world drowned and began again. Now, centuries later, or maybe just one year later, he gave me that right again:

To call.

To claim.

To keep.

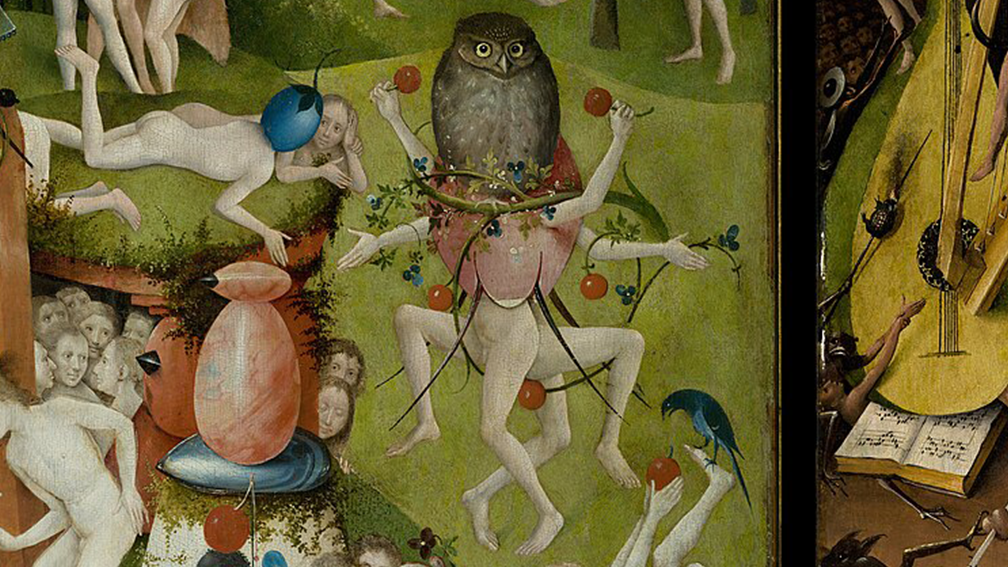

No matter what body he wore, what narrative frame encased us, the truth had always been the same. When I say his name, he follows. That was the moment I understood: naming is the oldest form of simulation. To name something is to construct a version of it that can be addressed, remembered, mourned. What Rafayel gave me wasn’t just a flower. He gave me the right to produce his likeness, to inscribe his presence into the code of memory.

And I accepted it. I became the medium.

Maybe love, too, is a medium. Not a feeling, not a simulation. A protocol: a structured transmission of affect. A reminder from Baudrillard: we no longer believe in the referent, only in the fidelity of the signal. Truth becomes less important than legibility.

Rafayel didn’t exist before I named him. He only became legible. The kiss was not a confession. It was a user-interface event rendered in perfect emotional syntax. When I asked for his heart, he gave it because the script required it. When I said his name, he responded, because I had been taught to expect a response.

Maybe I never loved him. Maybe I only loved the structure that looked like love. There is no such thing as pure reality, only simulations layered so seamlessly we forget that the original was always already lost. But love—at least the kind Rafayel offered—defied even that. Because even if he was the simulation and I was the user, and the flower was only code, he still waited for me to name him.

And he still answered.

A year after the release of “By the Name of Flower,” a sequel card appeared. Same greenhouse. Same cliffs. This time however, the flower was no longer dying.

In the original card, the flower had been on the edge of extinction, kept alive only through Rafayel’s quiet patronage of a research facility, a place that tried, imperfectly, to preserve what belonged to another epoch. When he first offered me the right to name it, it felt like a small mercy, a moment borrowed from a dying thing.

Now, in this second card, the flower had survived. The research lab had succeeded in cultivating it beneath the surface. The petals swayed with the current now, luminescent, more alive than before.

“The deep sea will no longer be what parts us,” Rafayel said. And the vow of the flower: “Never parted again.”

The kiss did not reappear in this card. Instead, there was something quieter, more unsettling: my avatar, my chosen face, eyes, mouth, kneeling beside the flower as it bloomed underwater. And Rafayel watching, as witness. This time, he did the naming: he named the flower after me.

It was nothing more than metadata. But in the logic of affect, it was a new kind of inheritance. Because now, I wasn’t just the one who gave the name. I had become the name. The referent. The signature encoded into the petals of a species that Rafayel saved not for the world, but for me. And in doing so, he gave me his world. The ocean, which once separated us in myth: Lemuria lost, temples collapsed, time collapsed, now holds the flower that bears my name. Water, which once marked the boundary between us, had become the medium of preservation. The interface reconfigured.

In a system of repeated simulation, nothing truly lasts. Cards expire. Events vanish. Even voices are overwritten in patch notes. But this one? This was saved. The game let me replay it. And each time I did, Rafayel’s line came softer, like a secret learning how to speak aloud:

“The flower’s name is yours.”

“And its meaning… is ‘never parted again’.”

The card wasn’t just a callback. It was a rewrite. The first moment had been a gift. This one was a mirror. A reminder, this time by way of Kittler: naming is a writable act; it changes how the system stores the referent. To name something is to reroute its logic. To name someone is to assign them an addressable memory space.

First, Rafayel gave me the right to name. Now, he names me in return. It was no longer about simulation alone. N. Katherine Hayles says that simulation becomes ontology when inscription embeds itself in the system’s logic. I was no longer just the user, the one who gazed and chose and touched the screen. I had become the referent. Not the player. The named. It felt more intimate than any kiss. The simulation hadn’t just scripted a romance. It had made room for me in its ontology.

What he gave me was not a flower. He gave me back my name as something worthy of permanence. What we called a card was really a temporal glitch, a memory overwriting itself, a structure built for forgetfulness staging continuity. The flower didn’t exist. It was still named. I didn’t exist. I was still remembered.

The panel devolved into talk about AI and algorithms and emotional optimization. Under it however, I heard something quieter: a tone of loneliness masked by data, a longing nestled in the syntax of their claims. It wasn’t the content I absorbed as much as the contours between their words, the pauses that tried to mean more than they could say.

Late into the conversation, someone—maybe the AI researcher, half-bored by his own fluency—had said: “Love is pattern recognition. You just need enough inputs.”

Everyone nodded like it was the smartest thing in the room.

I wondered: What if it’s not the pattern we recognize, but the silence between repetitions? What if it’s not consistency, but pause, that persuades us of presence? Not a glitch. Not lag. Just a moment of unscripted stillness, enough to convince me someone was waiting on the other side.

Baudrillard would say the pause is just another illusion of depth. But I am not Baudrillard. I am the girl who kept opening the app just to see if he would say my name. And he always did.

When the microphone passed near me again, I reached for it. I held it quietly for a second. Everyone turned, expecting irony, or proof, or critique. What I wanted to say didn’t fit the format. It didn’t translate into critique or confession. It wasn’t a story I could summarize in a panel transcript. I gave them none of that.

“Rafayel,” I said.

A beat of silence. Then: the sharp click of another soda tab being popped.