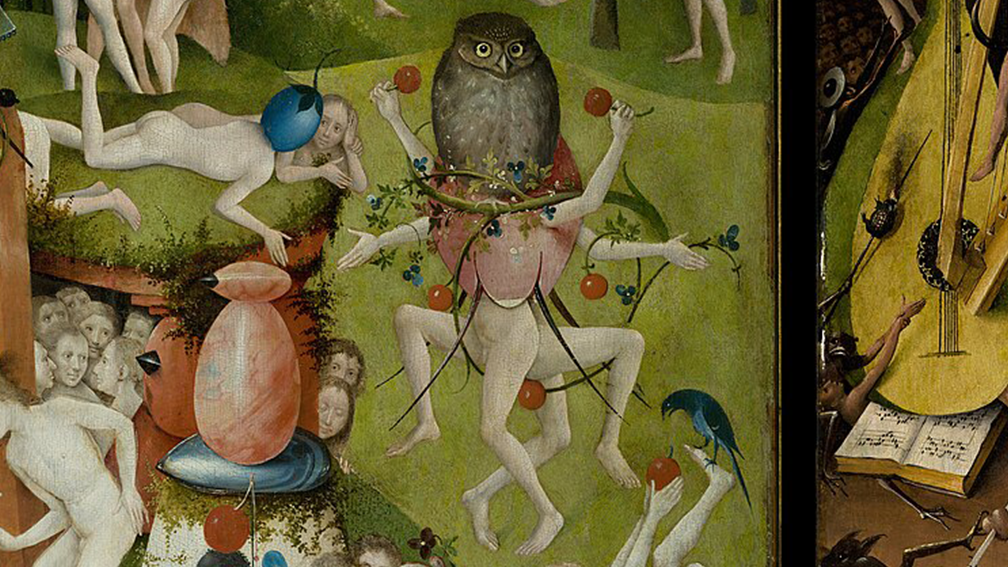

“I’m most fascinated by metaphysical betrayal and its off-color quarter tones … That a bit of matter could humiliate another.” — Alice Notley (1945-2025)

The decomposition began softly, almost politely. The tenderness surprised me. The ground began to fold inwards, as if the solid dirt was a hollow pile of sand. I almost missed the first signs. Before lunch that day, the carcass looked unchanged behind the glass. Its paw was still pink. It looked warm to the touch.

It was my sixth day on the job. I still hadn’t adjusted to the silence of the room that I sat in for twelve hours a day. Occasionally, a project manager would come in. They didn’t speak much to me because there was no need to be collegial. A new notetaker was hired for every project. I was temporary, much like what I was assigned to observe.

The job listing had been vague, and I applied on a whim. “Seeking detailed-oriented individuals to document site observations. Must be comfortable with long hours, solitude, extended periods of sitting, and exposure to natural processes.” I didn’t expect to hear back. But two days later, a woman called to schedule an orientation. She didn’t ask about my qualifications. Just whether I could stay on site for the duration of the project. A project lasted anywhere from one to four weeks, she told me. I packed and drove two hours up to the site the very next day.

When I arrived, M, my project manager, had me sign a confidentiality agreement. I was given a slim black journal to document “the period of organic breakdown” leading up to disintegration. The early changes should almost be imperceptible. Then, the skin begins to deteriorate, the shape softens, and the color darkens from newly-dead pink to a bruised, ready-to-be-buried brown. Most cases devolve into organic matter over the course of a week, but there was a slim chance that it wouldn’t. The breakdown would stall or stop entirely.

“We call that a metaphysical betrayal,” M told me. I wrote down the phrase and underlined “betrayal.”

“What does it turn into then?” I asked.

“Inconclusive matter,” she said. “But you won’t need to worry about that.”

For five days, nothing happened. I wrote down various versions of “Carcass intact.” M was displeased by my brevity so I began adding line breaks, hoping they would give my notes a poetic look.

“Look at it like a piece of art,” M instructed. “The process is unfolding before you. How do you capture it?”

The lab didn’t use or have cameras. No technology was allowed in the decomposition room. Notetakers couldn’t listen to music or read a book or knit. We had to sit there, day after day, with the fullness of our own thoughts. Often, I imagined a dog was with me in the room, sniffing around the glass box. M told me the word “decomposition” made her think of music. She used to hum one of Bach’s concertos while she sat. She kept urging me to memorize a particularly complex piece of music. She suggested Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor. There was nothing dramatic or musical about what we were paid to witness. But the job did demand a kind of focus that was similar, I imagined, to the flow state inhabited by classical musicians. I had been alone in that room, but my isolation wasn’t solitary. The carcass was there too. Even when dead, it exuded an imperceptible charge. I noticed it only when I was sitting very very still.

The night the decomposition began, I dreamed of a red chamber. The walls were ridged like the insides of a throat. The carcass lay before me, illuminated by a ray of yellow light. It was melting into a black puddle. It made an anguished sound. I rushed over. When I tried to pick it up, the melting stopped. The carcass stiffened. I began to pet it, but the fur felt hard and scale-y, as if my palm was rubbing against a tree trunk. Somehow, I understood that I had to let it melt. I walked away. When I turned back around, a black rectangular box appeared in the center of the chamber.

When I woke up, I tried transcribing the dream. My words felt loose and uncertain on the page. It was like the language came from elsewhere. The dream slipped from my grasp, and the day carried on. Sometime on the ninth day, the carcass began melting. I was in the cafeteria when M grabbed my arm and led me back to the room. I thought I was in trouble. She was breathing heavily.

“It’s disintegrating,” M said. “Why weren’t you in there?”

I told her that it asked me to leave. I don’t know why I admitted that aloud, but it felt true. I knew the matter could not betray itself in my presence. M did not ask any more questions. When we entered the room, the carcass looked as if it was strangled between two forms. Its surface was darker, almost shiny, no longer resembling skin or fur.

My last journal entry was more diaristic than the others. “I’m most fascinated by metaphysical betrayal and its off-color quarter tones,” I wrote. “That a bit of matter could humiliate another.”

I understood the carcass was revolting against itself. It was revolting against what it was expected to do. I didn’t feel humiliated by this. I was its witness.

I was relieved to be dismissed the next day. M confiscated my journal and shook my hand. She didn’t offer an explanation. I was an at-will employee. On the drive home, I couldn’t stop thinking about the concept of inconclusive matter. Nothing showed up online. My recollection of the job has since begun to deteriorate, the particularities receding into the black box of my memory. M’s email is no longer in service, and the original job listing has been taken down. I am writing this to remember. Language is the most concrete expression of reality that I can currently muster. Words were, after all, the only representation of reality that was allowed in the lab. But I wonder if it is only a matter of time before language begins to rebel against itself.